I’ve been meaning to write some notes about work for a while now but… well… work keeps getting in the way. Weekends come round fast but they’re over too soon, and then it’s back to work. Rinse and repeat. A life lived out in fits and starts to a rhythm of resentment. It’s not just me. It’s a sensation familiar to anyone who’s ever been caught up in waged work. But perhaps I’ve been feeling it more acutely of late, probably as a consequence of getting older, thinking more about mortality as I close on the finishing line (don’t even get me started on pensions).

Remember when computers were going to herald an age of leisure? Yet as everyone knows in their bones, we spend more hours working now than ever. It’s easy to think of capitalism as an economic system built around the need to generate profit, but actually it’s more than that. Capitalism is a mode of production that controls and dominates human beings by putting us to work – whether that work is waged or unwaged, ‘free’ or forced. To paraphrase the opening line of Capital, the wealth of societies in which the capitalist mode of production prevails appears as an “immense collection of jobs”. Capital is a beast that must be fed; or perhaps we can flip that on its head and think of human beings as the beasts whose desire for freedom must be tamed, controlled, channelled or suppressed.

But if work is the problem, it’s still incredibly hard to imagine a world without work. And that’s partly… well… because of work. It structures our lives, it structures our bodies, it structures who we are. And it stunts our imagination. Years ago I remember a meeting around climate change where a few of us were trying to argue that the refusal of work should be put at the heart of the discussion. There was resistance, with some arguing quite passionately that the work they did in their everyday jobs was actually quite socially useful. And there’s the problem. The idea of ‘work’ conflates a whole bundle of things: there’s work, labour, meaningful human activity, and the stuff that we need to do to survive. It’s not even that these are separate activities: my average 9-to-5 of wage-labour involves all four. And that’s no accident.

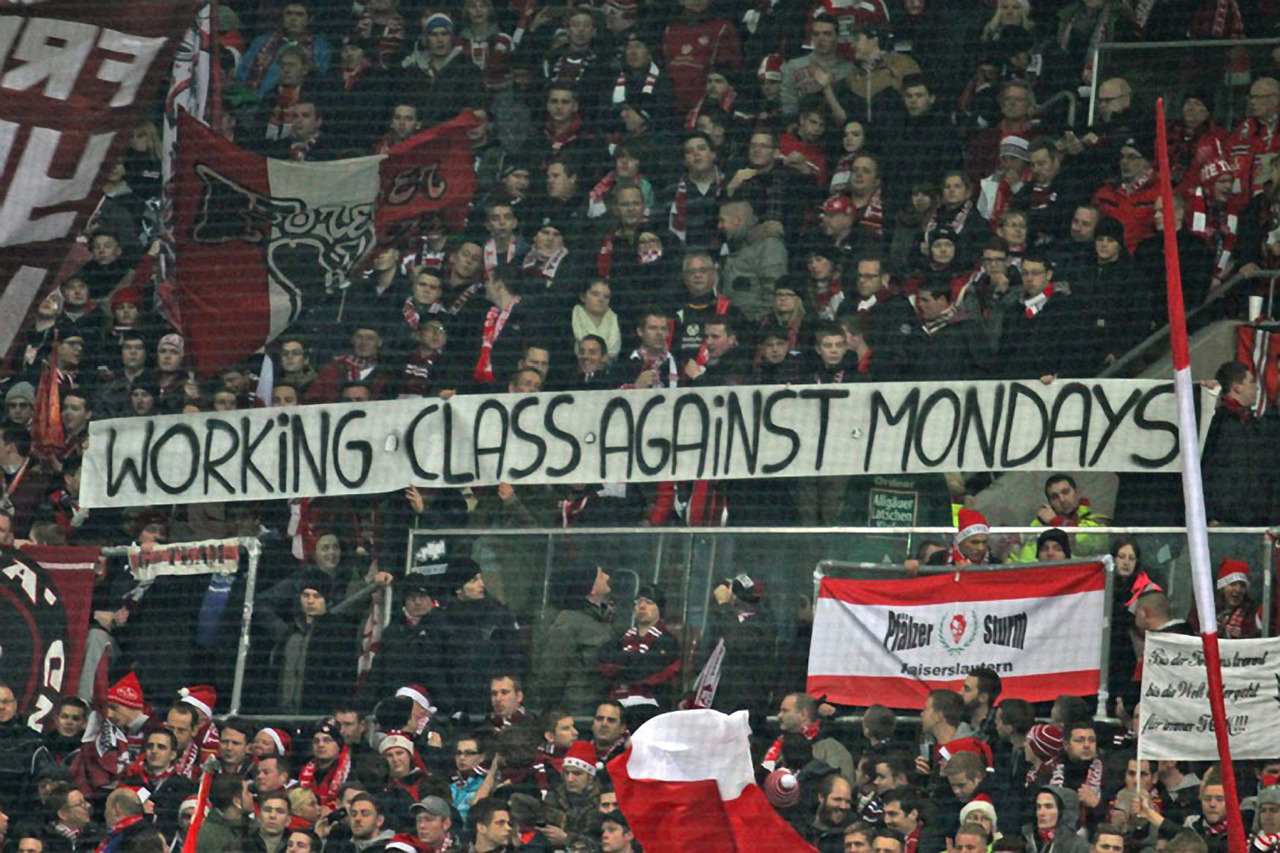

The ceaseless imposition of work isn’t just about forcing people into wage-labour force by driving them off the land and into cities. It’s not just about making people in jobs work longer and harder. It’s also about the way that capital tries to squash all human activity into something that follows a pattern set by wage-labour. ‘Leisure’ is a perfect example. On the face of it, it’s about time spent away from the constraints of wage-labour. Whether you work as a teacher, as a nurse, or as a builder, leisure is set up to be your escape route: your work becomes what you do to meet your basic needs and allow you to fulfil your desires. Living for the weekend. But as a mirror image of work, the idea of ‘leisure’ is no less alienating. Separating ‘need’ from ‘desire’ like this is always going to end with a fucked-up relation to reality. How do we fit them back together so that Sunday is no different from Monday?